The global energy landscape is undergoing its most profound transformation since the initial rollout of electrification over a century ago. The traditional power grid a one-way street delivering electricity from massive centralized plants to passive consumers is rendered obsolete by modern demands. It is being replaced by the “Smart Grid,” a dynamic, digital ecosystem that facilitates two-way communication between utilities and customers, integrates decentralized energy sources, and utilizes advanced sensing to ensure reliability.

The Smart Grid Market is no longer a futuristic concept; it is a present-day industrial imperative, driven by the converging necessities of climate change mitigation, infrastructure modernization, and the digitalization of the economy. This article provides an in-depth analysis of the market drivers, technological pillars, emerging trends, and challenges defining this critical sector.

Market Overview: The Nervous System of Energy

At its core, a smart grid applies information technology to electric power generation, transmission, and distribution. Unlike traditional grids that operate largely “blind” until a failure occurs, a smart grid utilizes a vast network of sensors, smart meters, and automation software to monitor operations in near real-time. This digital layer allows for self-healing capabilities, predictive maintenance, and the dynamic balancing of supply and demand.

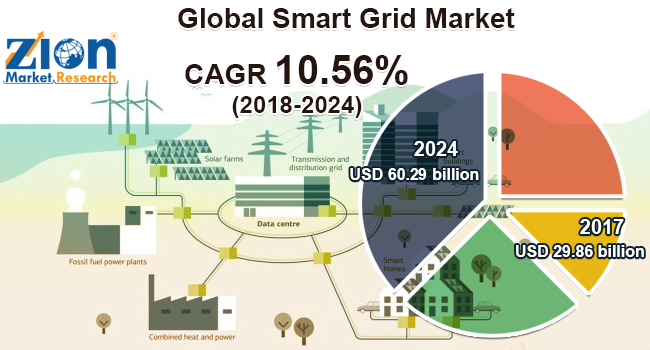

The market for smart grid technologies is experiencing robust growth, projected to reach hundreds of billions of dollars in valuation over the next decade. This growth is not uniform; it is characterized by massive investments in hardware (meters, sensors), software (analytics, management systems), and services (integration, consulting).

Key Market Drivers

The urgency to transition to smart grids is fueled by several irreversible macro-trends:

1. The Integration of Renewable Energy and DERs The rapid shift toward solar and wind power is the primary catalyst for grid intelligence. Traditional grids were designed for steady, predictable baseload power. They cannot easily handle the intermittency of renewables (e.g., clouds blocking solar panels or wind dying down) or the reverse power flows caused by Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) like residential rooftop solar. Smart grids use real-time data and automated controls to balance these fluctuations instantly, preventing blackouts and ensuring stability.

2. Aging Infrastructure and Grid Reliability In many developed nations, particularly in North America and Europe, grid infrastructure is nearing the end of its operational lifespan, resulting in increased frequency of outages and significant efficiency losses. Utilities face a choice: replace like-for-like, or modernize. The smart grid offers a pathway to replace aging assets with intelligent ones that improve reliability through “self-healing” technologies—automatically rerouting power around faulted grid sections to minimize downtime.

3. Government Mandates and Incentives Governments worldwide are actively pushing smart grid adoption to meet carbon reduction targets. Policies ranging from the EU’s energy directives to the US Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provide the necessary financial backing and regulatory frameworks to de-risk these massive capital investments for utilities.

Technological Pillars of the Market

The smart grid is not a single device, but a convergence of technologies:

-

Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI): Often the first step in modernization, smart meters provide a two-way communication channel between the consumer and the utility. They enable time-of-use billing, remote disconnect/reconnect, and provide utilities with granular data on consumption patterns.

-

Grid Automation and Sensing: This includes devices like Phasor Measurement Units (PMUs) that sample voltage and current thousands of times per second, giving operators wide-area situational awareness. Automated feeder switches and smart substations allow for rapid, remote control of grid operations.

-

Grid Analytics and Software: The “brain” of the operation. As megatons of data flow from sensors and meters, advanced software platforms, increasingly powered by Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), are required to process this information to forecast load, optimize asset maintenance, and manage outages.

Emerging Trends Shaping the Future

The market is evolving beyond basic metering towards advanced applications:

1. The Electrification of Transport (EVs) The widespread adoption of Electric Vehicles presents both a massive challenge and a significant opportunity. Unmanaged, simultaneous EV charging during peak hours could crash local grids. However, smart grids enable “Vehicle-to-Grid” (V2G) technology, turning EVs into mobile battery storage units that can discharge power back to the grid during peak demand, stabilizing the system.

2. The Rise of the “Prosumer” and Microgrids Consumers are becoming producers (“prosumers”) through on-site generation and storage. The smart grid is advancing to manage decentralization, leading to the rise of microgrids localized grids that can operate independently from the main grid during emergencies, enhancing community resilience.

3. Cybersecurity as a Market Segment As the grid becomes digitized, its attack surface expands exponentially. The convergence of Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT) makes utilities vulnerable to cyberattacks that could cripple national infrastructure. Consequently, specialized grid cybersecurity solutions are becoming a critical, high-growth segment of the overall smart grid market.

Challenges and Restraints

Despite the momentum, the path to a fully realized smart grid is fraught with obstacles:

-

High Upfront Capital Costs: Modernizing a national grid requires immense investment. The debate over who shoulders this cost—utilities, taxpayers, or ratepayers—often slows deployment.

-

Regulatory Lag: Technology is evolving faster than policy. Outdated regulatory frameworks often incentivize utilities to invest in capital assets (poles and wires) rather than operational efficiency solutions (software and data), hindering smart grid ROI models.

-

Data Privacy and Interoperability: Collecting granular household energy data raises privacy concerns. Furthermore, ensuring that equipment from dozens of different vendors can communicate seamlessly (interoperability) remains a significant technical hurdle.

Conclusion and Outlook

The Smart Grid Market is at an inflection point. It is transitioning from an “early adopter” phase characterized by pilot projects and basic meter rollouts to a mature phase of large-scale deployment and sophisticated analytics.

The future of energy is undeniably digital, decentralized, and decarbonized. The smart grid is the essential infrastructure required to make that future work. While challenges regarding cost and regulation persist, the immense operational benefits, coupled with the undeniable imperative of climate change adaptation, guarantee that smart grid technologies will remain a dominant area of industrial investment and innovation for decades to come. The grid is not just getting an upgrade; it is being re-architected for a new energy era.

Other Report Zion Market Research:

https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/de/report/plastic-pigments-market

https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/de/report/c4isr-market

https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/de/report/medical-equipment-maintenance-market

https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/de/report/digital-inks-market

https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/de/report/pet-services-market